As someone who has been fascinated with the royal family for several years — a girl needs her guilty pleasures! — it might seem odd that I didn’t write a newsletter last week about Spare, Prince Harry’s best selling memoir. After all, I’ve already written many newsletters about the royal family. With book reviews on the front page of every newspaper and the top item on the evening news, why wouldn’t I jump on the bandwagon and spill the tea?

I chose to step back for a while, because I like to keep the chaos monkey out of my head. I preserve my own mental health by not getting involved with other people’s mental health issues. Trying to make sense of Harry’s thoughts would be an exercise in frustration, like sorting out one of those infinite mazes in an Escher painting.

Without getting into the weeds of Harry’s particular issues, let’s just talk about recovering from tragedy. All of us eventually have to deal with “bad things” in life and we have a choice about how we deal with those experiences: do we let those experiences define us or do we move on?

Beginning with the Netflix show, it started to become obvious that Harry wasn’t the good natured goofus portrayed in the press. Instead, he was a very angry man with a strange obsession with his mother and paranoid delusions about the press. (Wrote about it here.) The excerpts of his memoir and clips of interviews make it clear that the Netflix show didn’t scratch the surface of Harry’s problems.

Harry believes that he remembers his mother talking to the midwife, while she was delivering him (!), and that she shared the name of his future wife. Destiny! He’s convinced that his family told lies about him to the press in order to promote themselves. A man with millions in the bank, he feels destitute. He says that his mother is more magical than Mother Theresa. The crazy train rolls on. I’ll let the book reviewers recount all those details.

As a parent, I can’t help but put myself in Prince Charles’ shoes. How would I have handled this broken boy? I suspect that a boarding school wasn’t the right place for him; rather, he needed years of long walks and deep hugs. In this one area, Harry’s issues are not unique to him. Tragedies happen all the time, and there’s no way to totally protect vulnerable children from sad things that happen in life.

When Cousin Robbie was nine, he found his mother in the basement, after she blew her head off with my uncle’s handgun. My mother was raised by an alcoholic. My dad’s father died from a freak virus two months before he was born, so he was surrounded by a family with clinical depression and his own massive paternal void.

Truthfully, Robbie and my parents have scars from those traumas. I don’t think anyone walks away from such sadness during critical years without some shadows. The trick is, I think, to make those scars part of your story, just not the whole story. My son’s autism is part of my story, but not how I define myself.

As an adult, Harry is now responsible for his own mental health. There’s only so much blame that he can place on his father. And Harry isn’t dealing well. He is entirely defined by his tragedy, even calling his book after a derogatory nickname that he’s given himself. He’s a disgruntled postal worker with a gun collection.

I do wonder if his dysfunctions, his perpetual wallowing in woes, is due to his extreme privilege. If you HAVE to earn money to pay the rent and take care of the children, then you can’t think about the past and allow your brain to obsess over small slights. Harry always had a roof over head and food in his belly and too much time to let problems fester. Of course, middle class people have mental health issues, too, but I do wonder if Harry would be less crazy if he had a purpose in life.

In many ways, it’s hard to find the big picture in Harry’s story, because he has nothing in common with anyone else on the planet. None of us will ever live in a castle or have a $35 million wedding. I simply cannot comprehend the life of someone sent to a boarding school at a young age, who waves to crowds from horse drawn carriages, and struts around in sashes and epaulets.

The only thing that we can learn from Spare is what not to do — don’t throw your entire family under the horse drawn carriage, find a new life after a tragedy, find your own place in life without comparison to others, and surround yourself with healthy people.

LINKS

How much do I love Jennifer Coolidge?

I froze my todger.

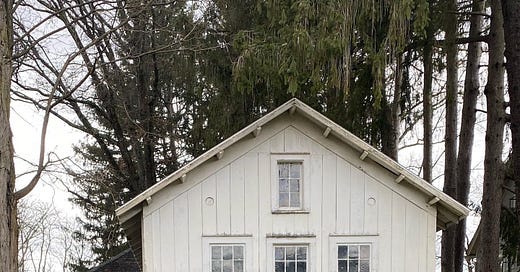

Last weekend, we hiked around New Paltz, NY for the day and made homemade pasta on Sunday. More picture here.

I wrote about time on my disability newsletter:

Watching: The Crown, 1923, Yellowstone

Cooking: Non-dairy cream of mushroom soup, Squash and Chickpea Curry